Cynthia A. Williams is Visiting Professor of Law at Indiana University Maurer School of Law and Professor of Law Emerita at the University of Illinois College of Law; and Robert G. Eccles is Visiting Professor of Management Practice at Oxford University Said Business School. This post was authored by Professor Williams, Professor Eccles, Nathan Chael, Christy O’Neil, and Alex Cooper.

Introduction

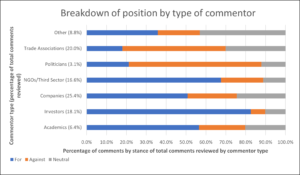

In June, the comment period closed on the SEC’s proposed rulemaking on “The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Financial Disclosures” (the Proposal). The SEC received more than 5,000 comments on the Proposal. The Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative has conducted a review and analysis of the more than 1,000 comments made by trade associations, politicians, NGO and third sector entities, companies, investors and academics, as well as lawyers, professional organisations, regulators and standards bodies (these latter four groups are categorised as Other in the chart below as the absolute numbers are relatively small). Form letter comments and comments made by individuals were excluded from the review on the basis that the review focused on certain arguments which were not commonly addressed in such comments.

The review classified the major arguments used in each comment, but focused on arguments related to legal authority, Scope 3 emissions disclosures, and materiality and the 1% threshold. The review also categorized every commentator as For, Against, or Neutral with respect to the Proposal in general terms; a commentator who made suggestions in relation to the Proposal may have nevertheless been categorised as generally For the Proposal. This article summarises the key findings of the review at a high level.

*Please note that this graph does not include the comments reviewed that were not identified as having a stance (for example, as they were requesting an extension to the consultation period), and consequently, the percentages in the column on the left in the above graph of the total comments reviewed do not equal 100%.

The graph above shows the stances on the Proposal adopted by different commentators, and, in the column on the left, as a percentage of the total comments included in the review. Investors are most supportive, followed by NGO/Third sector and then Companies. Academics are also generally supportive. Least supportive are Trade Associations and Politicians.

The SEC’s Authority and Duelling Comments by Academics and Former SEC Commissioners

Commentators of different types referred to the SEC’s authority in their submissions (see, for example, Impax Asset Management L.L.C., the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Mining Association). Of particular note are the duelling comments submitted by groups of former SEC Commissioners and senior lawyers. One group of five former Commissioners, including former SEC Chairs Richard C. Breeden and Harvey L. Pitt, argued that the Proposal represents an abuse of the SEC’s mission and that the SEC will almost certainly be found in court to have exceeded its legal authority. For these former Commissioners, the Proposal is a wolf in sheep’s clothing—an attempt to conduct substantive greenhouse gas emissions regulation through an agency wholly unrelated to that purpose. “It beggars belief,” they write, “that Congress would have delegated to the Commission the authority to set substantive climate policy through entrusting to it the authority to prevent fraud and ensure orderly markets.” This set of former Commissioners believes that, while the SEC may not be strictly limited to requiring material disclosures, the Proposal nonetheless goes well beyond what it may do to serve the public interest. For them, “the Proposal represents an unprecedented and unjustified effort beyond financial materiality and engages the Commission in matters beyond its statutory remit.”

In contrast, a second group of eight former SEC Commissioners and Chairs, including former SEC Chairs Arthur Levitt, Mary L. Schapiro and Elisse B. Walter, along with five SEC General Counsels and four Directors of the Commission’s Division of Corporation Finance and a number of legal academics and senior practitioners, submitted a letter defending the SEC’s authority to promulgate the Proposal. This comment stated that “there is no legal basis to doubt the Commission’s authority to mandate public-company disclosures related to climate.” For this group, the Proposal is not “unprecedented” in any way that would throw its legality into question. Instead, they trace the history of the SEC’s promulgation of requirements for companies to disclose different categories of environmental information since 1975. In their view, while the Proposal, like any new regulation, contains new particular requirements, “the Commission, courts, and practitioners have understood for decades that the SEC’s statutory mandate includes authority to require environmental and climate-related disclosures.”

A number of law professors also traded arguments about the SEC’s authority to require the Proposal’s disclosures. A group of 30 law professors led by Penn’s Jill Fisch and Emory’s George Georgiev wrote that the U.S. securities disclosure regime necessarily evolves with the market, and that the Proposal shows the SEC responding to investors’ evolving needs for corporate climate governance and risk information, rather than a rule intending to regulate climate policy. Responding directly to this group, another group of 22 law school professors argued that while the SEC does have “broad statutory authority” to compel disclosures to protect investors, the latent but clear intent of the Proposal is to advance social goals related to climate change rather than protect actual investors. The SEC’s constitutional authority to compel the Proposals contemplated in the disclosure under the First Amendment was also discussed in the comments, including by law professors Sean J. Griffith and J.W. Verret.

Scope 3 Disclosures

One area of particular controversy was the SEC’s proposal to require companies to disclose their Scope 3 emissions, but only where an entity has a goal covering Scope 3 emissions or where Scope 3 emissions are material. (Scope 3 emissions are those emissions created in companies’ supply chains and by the use of companies’ products.) This proposal prompted a range of responses. At one end of the spectrum, over 100 comments from commentators including asset managers/investment companies and NGO/Third sector entities generally supported broader Scope 3 disclosure (see, for example, CalSTRS, Engine No.1, As You Sow , Green Century Capital Management, Inc., and Oxfam America), including recommendations to extend the reporting requirements to smaller entities, and require third-party assurances for Scope 3 emissions disclosures. Several commentators, such as U.S. Impact Investing Alliance, expressed a preference that disclosure of Scope 3 emissions should be done on the same basis as proposed for Scope 1 and 2 emissions (i.e. removing the materiality threshold).

In contrast, over 200 comments reflected support for a narrower requirement. For example, the Federal Regulation of Securities Committee of the Business Law Section of the American Bar Association, while generally supportive of the Proposal, recommended that disclosure of Scope 3 emissions should be limited to situations in which such disclosures are material, and that the extent of Scope 3 disclosures should be limited to more easily quantifiable or estimable categories. Some asset managers including Fidelity and State Street Corporation stated the Scope 3 emissions disclosures should remain voluntary (at least until potential data issues could be resolved); similarly, others, such as Inclusive Capital Partners L.P., suggested that “Scope 3 implementation should be delayed to 2027” (see also Center for Sustainable Business at the University of Pittsburgh).

The potentially adverse effect of Scope 3 disclosures on smaller entities was highlighted. The American Trucking Associations, for example, noted how “[s]mall trucking companies have neither the expertise nor the resources to conduct Phase 3 assessments or estimates, accumulate and enter data, or contract with third parties”. In contrast, Green Century Capital Management “believe[s] that demand by large accelerated and accelerated filers for the tools, data, and services necessary to develop and report on Scope 3 emissions will facilitate the reporting of Scope 3 emissions by smaller entities.” Some commentators also referred to the SEC’s role as it pertains to privately-held entities within a registrant’s supply chain (see the American Securities Association and International Dairy Foods Association). According to the International Dairy Foods Association, “the proposal will place the market burden of measuring, reporting and verifying that data on private companies not within the SEC’s jurisdiction” (original emphasis).

Specific difficulties relating to Scope 3 disclosures were also noted. Eversource Energy referred to “the level of complexity and impracticability of verifying Scope 3 disclosure requirements” and the Food Industry Association suggested that “[a]s it stands, data confidence around the collection of Scope 3 data would likely rank low in the food industry”. The International Energy Credit Association also referred to the need “to acquire and disclose information from third parties and make public data and business plans that are proprietary.” This can be contrasted with the view that Scope 3 disclosures are being made by some entities already (see Private Equity Stakeholder Project). Given these alleged difficulties, it is perhaps unsurprising ‘safe harbor’ provisions for Scope 3 emissions disclosures were suggested by some commentators (see Workday and Empire State Realty Trust, Inc.). Furthermore, according to the Coalition for Renewable Natural Gas, “[t]he SEC provides no guidance as to how to determine if Scope 3 emissions are material.”

Materiality and the Proposed 1% Threshold for Financial Statement Disclosures

At least 400 comments referred to the materiality concept. Some commentators, in particular trade associations, operating companies and NGOs, opposed the notion that firm-specific greenhouse gas emissions could be considered financially material (see for example, ConservAmerica, American Enterprise Institute, the Cato Institute, Marathon Oil Corporation and the First Commonwealth Financial Corporation). Others, in particular investors, identified climate risks and the disclosure of information on issuers’ progress towards climate goals as being material. For example, the Vanguard Group stated that “we consider climate risks to be material and fundamental risks for investors and the management of those risks is important for price discovery and long-term shareholder returns.” Indeed, the materiality of climate risk was referred to in other comments from the investment sector (see, for example, Pacific Investment Management Company L.L.C., Aviva Investors and Fiduciary Trust International).

Materiality also arose in relation to the proposed 1% threshold for financial statement disclosures, under which climate change-related information would be disclosed in financial statements if that information could have at least a 1% impact on “a line-by-line basis.” A critique that was raised was that the threshold may lead to investors receiving immaterial information (see Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. and Warner Music Group). Indeed, Moody’s Corporation found that “[t]his disclosure would … necessarily vary across companies, leading to inconsistency and lack of comparability, inhibiting the usefulness of this information to investors and other market participants” (see also Grupo Bancolombia). Taking an alternate view, Impax Asset Management, L.L.C. stated that in relation to the proposed threshold, “the SEC was wise” and “[t]oo often, we have seen that companies take an atomistic approach to materiality.”

Some commentators argued that the 1% threshold would be inconsistent with the materiality principle; “[a]s proposed, the financial statement metrics place a disproportionate lens on impacts related to climate above all other material impacts to a registrant and its financial statements” (BDO USA, LLP. See also, for example Energy Transfer, L.P). Some commentators proposed that the threshold be replaced with the established materiality test, perhaps following “the SEC’s own recent Regulation S-K reforms for “materiality-focused” and “principles-based” discussions in Form 10-K’s MD&A; …” (CRE Finance Council and others, and see also PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, Institutional Shareholder Services Inc., Bank of America and ICAEW). However, several commentators, including Senator Reed and others, noted that the SEC has applied a 1% threshold for other reporting items, and argue that issuers are required to disclose information for each line item in their financial statements without considering materiality; and that therefore, the inclusion of climate-related risks without a materiality test would lead to less inconsistency across issuer reporting.

Some commentators noted that the proposed threshold contradicts the SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 99, which states that “[t]he FASB has long emphasized that materiality cannot be reduced to a numerical formula” (see Cleveland-Cliffs Inc.; see also Linklaters LLP, JLL and SEC Professionals Group). However, it may be that materiality could be determined with the aid of such a threshold; Senator Reed and others, for example, stated that SAB 99 “has suggested that accounting firms may apply a quantitative benchmark of 5% as a “rule of thumb” to develop preliminary assumptions about whether a misstatement or omission in a company’s financial statements is likely to be material” (see SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 99). Furthermore, KPMG stated in its comments that “[w]hile the disclosure threshold is not described as a materiality threshold, we believe the effect could be the same in terms of its application.” In this light, distinguishing between the proposed threshold and materiality may be unnecessary.

Conclusion

This review illustrates vastly divergent views within these categories. The challenge for the SEC will be to fashion a final proposal that strikes the right balance between the supporters and the objectors.

Print

Print